עיתונאיות ועיתונאים, הירשמו כאן להודעות לעיתונות שלנו

הירשמו לניוזלטר החודשי שלנו:

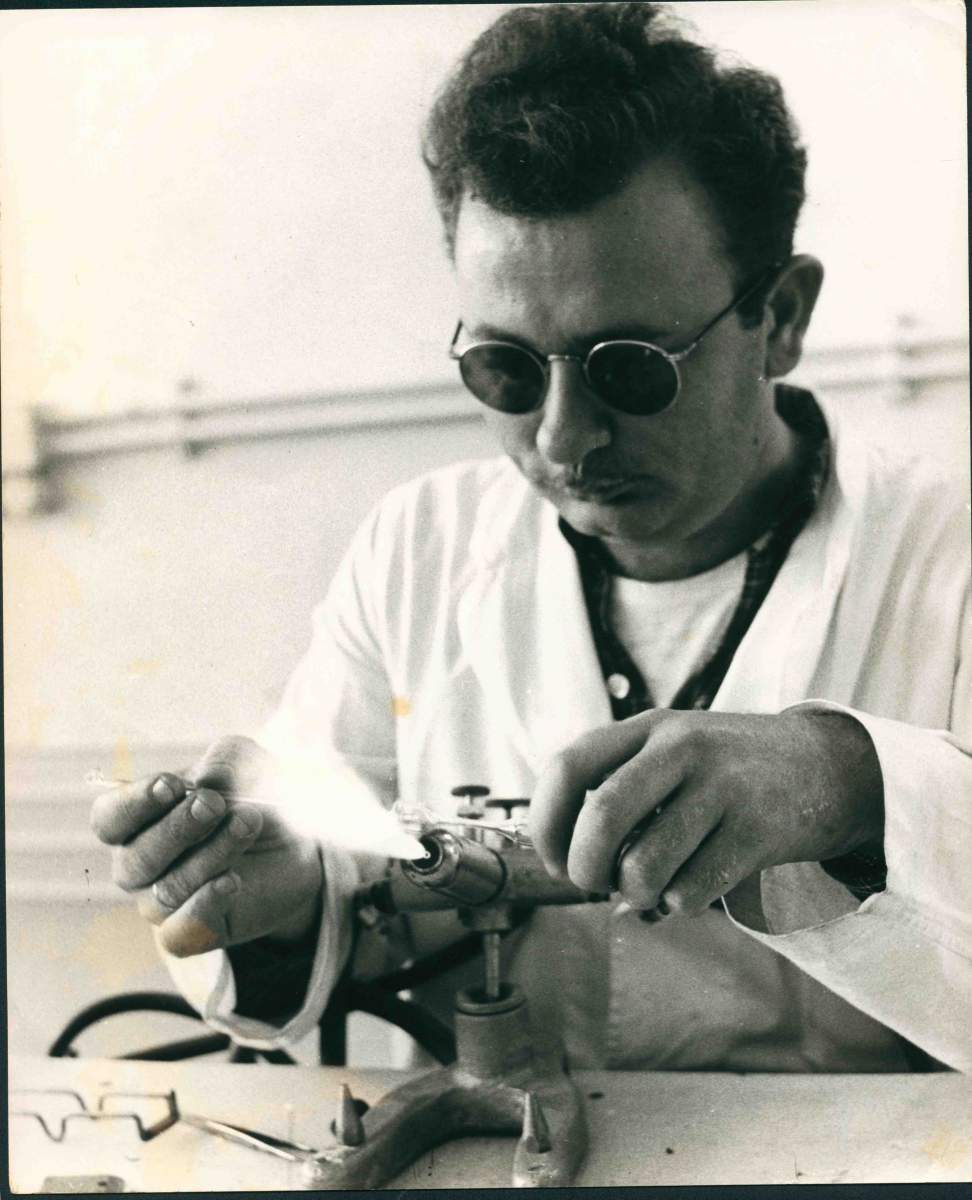

Yacob Meir Zilberstein, age 86, will soon be celebrating 70 years since he first started working at the Weizmann Institute of Science. He began his long career at age 17, in 1949 – the year the Weizmann Institute was established – as an assistant in the Isotope Department. While working at the Institute, Zilberstein trained as a glass-blower for scientific instruments, particularly vacuum systems. Over the years, he has been given credit in numerous doctoral theses, and he received an award for Outstanding Worker in the Faculty of Chemistry. His specialized skills have been so crucial that three months after he retired – in 1999 – he was asked to return to work. And he is still here.

Zilberstein’s story starts before his birth: “I was born in Mazkeret Batya (near Rehovot) in 1933. My mother was born in pre-state Israel; my grandparents came from Russia in 1882, lured by the initiative of the Baron de Rothschild, who wanted to create Jewish agricultural settlements in the land. After learning to farm at the agricultural school in Mikve Israel, they and another ten families founded Mazkeret Batya. My father came from Poland at age 20; his parents joined him here in 1933. They left behind two daughters and a son. The daughters survived the war, but their son and his wife perished in the Holocaust.

“I enrolled in a vocational high school in Tel Aviv, and moved there to live with my grandmother. But when the War of Independence broke out, our studies stopped and I found work at the Institute. My age was not a problem.

“There was a very special atmosphere in the Institute in those first years. There were few people and only a few buildings. Whenever Dr. Chaim Weizmann would travel abroad, we would all be called to the Sieff building, where he had his lab. We would stand in a circle in the lobby and he would walk around and shake each of our hands. When he returned, we would again gather round to shake his hand. That is a memory I treasure. I also remember his sister, Anna, who worked with him in his lab.

“I was drafted in 1951, and two and a half years later, I finished my service and was hired by the ministry of defense. They sent me back to the Institute, back to the Isotope Department, which was still headed by Prof. Israel Dostrovsky. Part of his research focused on mining ores in the Negev. But he was a major general in the army as well as a scientist at the Institute. He trained us to work in the Sorek (experimental) nuclear reactor. But when it was my turn to go work there, Dostrovsky vetoed it, saying: ‘No. You stay here.’ So I quit the defense ministry and once again became a worker at the Institute.

Whenever Dr. Chaim Weizmann would travel abroad, we would all be called to the Sieff building, where he had his lab

“I was sent to a glass-blowing course in Jerusalem, getting there by army jeep. Then I was flown to the Netherlands for advanced training. When I came back, I built huge tanks for heavy water and a complicated system for producing heavy oxygen from that water. It was the height of scientific advance for its day, but once there was no more need for that heavy oxygen, the whole system I had built was thrown away.

“In those years, the Institute had an entire glass-blowing department, but I belonged to the Isotope Department. I built lab equipment for all the members of the department, and I taught the students glass blowing as part of my duties. Over time, the Institute moved from glass to metal. But glass is still the best material for vacuum equipment. To get the same kind of hermetic seal with metalwork is difficult and time-consuming.

“I retired in 1999, and three months later I got a call asking me to return. They still needed the benefit of my years of specialized knowledge and experience. I came back to work two days a week. I always worked closely with the scientists, who brought me diagrams of the equipment they wanted for their experiments. They could buy standard things off the shelf, but for the special, complicated pieces, they came to me. Nowadays, I come in one day a week, and I do whatever is asked of me. I have gained a lot of experience in mechanics over the years and I’m good with my hands. I enjoy it when I can help the students with their problems.

“My departed wife, Sarah, was also an Institute employee. She was the secretary of Margalit Sela, and she was involved in establishing the first summer camp for science lovers in Israel and one of the first in the world. She loved to joke with me: ‘You’ve been at the Institute for so long, you should have been a doctor or professor by now.’

“Once upon a time, we called ourselves the ‘Institute family,’ and we felt like family. We all knew one another. I still have some good friends at the Institute, and we meet up once in a while. But now there is more distance between people – with several thousand students, staff and faculty, one can’t know everyone else. And the scientists spend more time with their computers – even using them to go to the Moon and stars – but they spend less time doing things with their hands.”