עיתונאיות ועיתונאים, הירשמו כאן להודעות לעיתונות שלנו

הירשמו לניוזלטר החודשי שלנו:

Is it possible to be right 100% of the time? This question haunted Alan “The Brain” Powers when his classroom welcomed an interactive talking whiteboard named Hugo. “The Brain” is the class genius in the animated children’s series Arthur, and Hugo, who claimed to be 100% accurate, triggered his skepticism. Indeed, as soon as the whiteboard corrected the teacher, Mr. Ratburn, it became clear that the promise of perfect accuracy was a stretch: Hugo was right only 98% of the time…

Researchers in the Science Teaching Department of the Weizmann Institute of Science are exploring similar realms as they try to develop new technologies that improve learning and instruction. When they ask teachers how artificial intelligence could support their work, the recurring answer is that they “could use help reviewing open questions.” This may sound like a futuristic fantasy – like Hugo from Arthur, or perhaps like a perfect teacher’s assistant who saves valuable time and provides valuable insights – but Dr. Giora Alexandron’s research group is currently developing just such artificial intelligence applications.

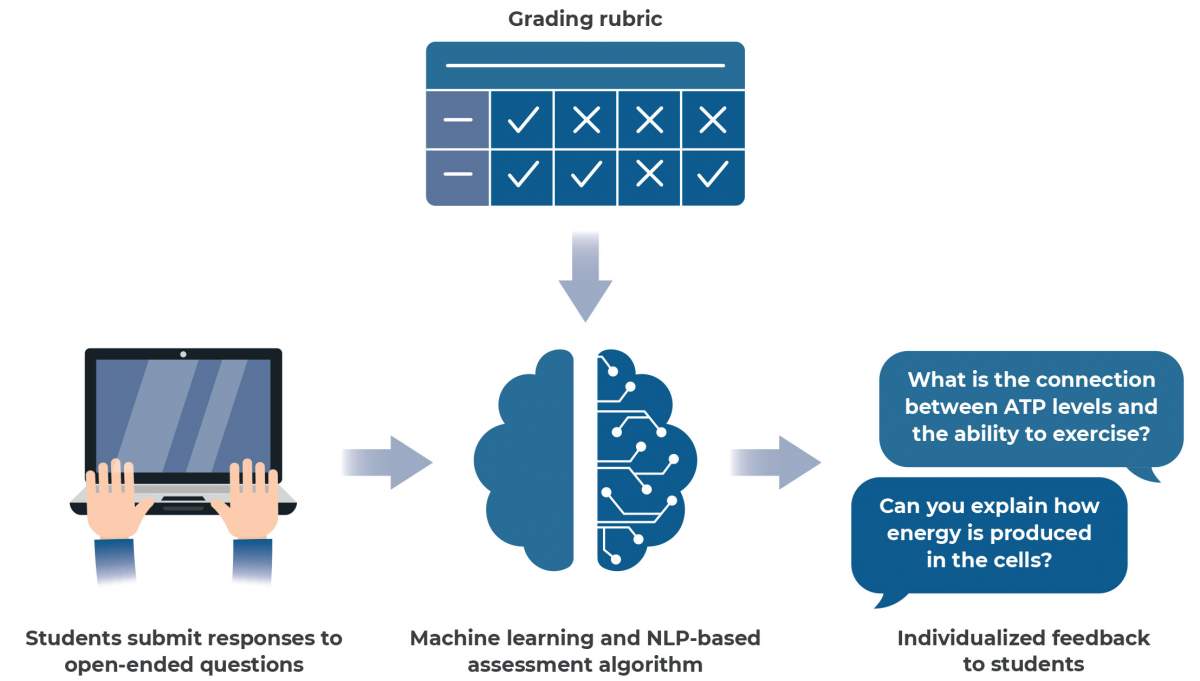

Recently, the research group published a study in which they showed that machine learning algorithms and natural language processing can be “trained” to automatically evaluate students’ responses to open biology questions. The algorithms’ evaluations were highly similar to those of pedagogical experts and teachers. In addition, the first experiments in which students and teachers received pedagogical feedback based on the machine-generated analysis showed that there was a marked improvement in learner achievement. While similar English-language research has already led to the creation of commercial products, this is the first study of the kind conducted in Hebrew.

The algorithms were found to do more than simply mimic humans: In some criteria, they did better. The machine-learning systems were better able to provide a quicker overview of the level of knowledge in the classroom.

The study was led by postdoctoral fellow Dr. Moriah Ariely, who specializes in the instruction of biology and in scientific writing, and by PhD student Tanya Nazaretsky, who specializes in the applications of artificial intelligence to science education. Dr. Cipy Hofman also contributed. The research was conducted in collaboration with the biology education research group led by Prof. Anat Yarden. It was performed with a pilot group of biology teachers and was run on the PeTeL (Personalized Teaching and Learning) platform – a digital learning environment developed at Weizmann’s Science Teaching Department, which is being used by hundreds of teachers and tens of thousands of science students across Israel.

Just as “The Brain” learned from his encounter with Hugo, there is no alternative to Mr. Ratburn, the wise teacher who guides the students. “The COVID-19 pandemic has indeed accelerated the adoption of distance learning technologies, but many studies have shown that human guidance is irreplaceable,” says Dr. Alexandron. “There’s no doubt that the ideal role of technology in education is to empower and support learning and instruction processes led by teachers.”

Based on this insight, the research group is taking studies on the human factors that shape teacher-artificial intelligence interactions in a new direction. They are conducting this research together with Professor Mutlu Cukurova of University College London, who is an expert on computer-human interaction and has researched this subject in the context of finance and medicine-related recommendation engines. Many professionals, it turns out, suffer from cognitive biases that can lead to excessive trust in – or distrust of – recommendations generated by artificial intelligence.

"“Our vision is to see artificial intelligence work with and for teachers on their various tasks, helping them tailor their instruction to the particular needs of individual students"

Teachers, as the study revealed in a recent publication, are characterized by similar biases. For instance, teachers are reluctant to accept AI-based recommendations when these contradict their previous knowledge about their students. As the researchers showed in a subsequent publication, with proper training in the use of the AI system, and in the uncertainty that is inherent in its predictions, those biases can be decreased: Teachers can develop trust in the AI-powered recommendations and consider them in an informed manner.

In another study on teacher attitudes toward artificial intelligence, the research group conducted an experiment in the spirit of the television show The Masked Singer. In this experiment, students were asked to answer a set of open questions. Next, individuals from a group of biology teachers were asked to predict the kind of feedback the other teachers in the group would give on the students’ answers. The teachers were then asked to guess which of their peers – The Masked Teacher – was the best predictor. The teachers were in for a surprise: The Masked Teacher was revealed to be none other than the natural language-based AI algorithm that had learned from them how to evaluate student answers to open questions.

Insights from this study inspired the design of another technological system: GrouPer, an interactive tool that allows teachers to map students according to knowledge profiles. GrouPer was developed in collaboration with the Physics Education Research Group headed by Prof. Edit Yerushalmi and a group of pilot teachers who helped tailor the tool to the affordances and constraints of their various classroom environments. Dr. Asaf Bar-Yosef, Dr. Michal Walter and Carmel Bar also took part in the design of GrouPer. The technological development was led by Nadav Kavalerchik, and the interface was designed by Edna Rolnick.

Despite the promising results and the enthusiasm of the teachers who participated in the experiments, the widespread adoption of these innovative tools faces technological, financial and practical difficulties. “Our vision is to see artificial intelligence work with and for teachers on their various tasks, helping them tailor their instruction to the particular needs of individual students. The goal is for algorithms and data to facilitate pedagogical expertise. Good teachers are irreplaceable,” Alexandron stresses. “Our goal is to give them the tools that will empower them and help them – and their students – to excel.”

Dr. Giora Alexandron's research is supported by the Maurice and Vivienne Wohl Biology Endowment and the Estate of Emile Mimran.