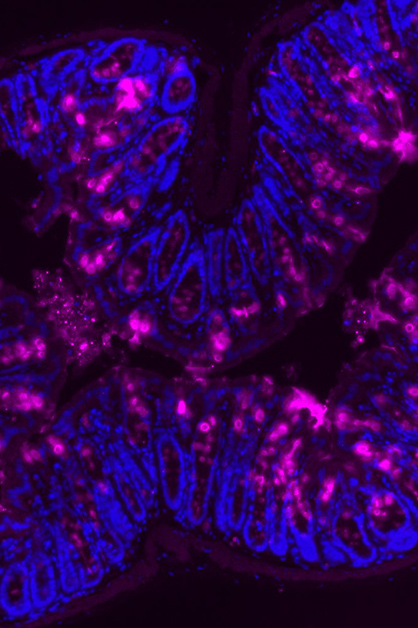

The mucus in the human body is much more than mere slime. Covering vast areas, one type of this smart material protects our lungs by filtering out hazardous microorganisms while enabling the exchange of gasses. In the inner lining of our intestines, another type of mucus, also covering a huge swath of the body – the size of a tennis court in an adult’s gut – keeps unwanted materials out of our internal organs while letting through the nutrients and fluids we require.

In a new study, Weizmann Institute of Science researchers have discovered that intestinal mucus performs yet another crucial but unexpected function: It can catch, convert and bring safely into our cells a potentially toxic yet necessary material – copper.

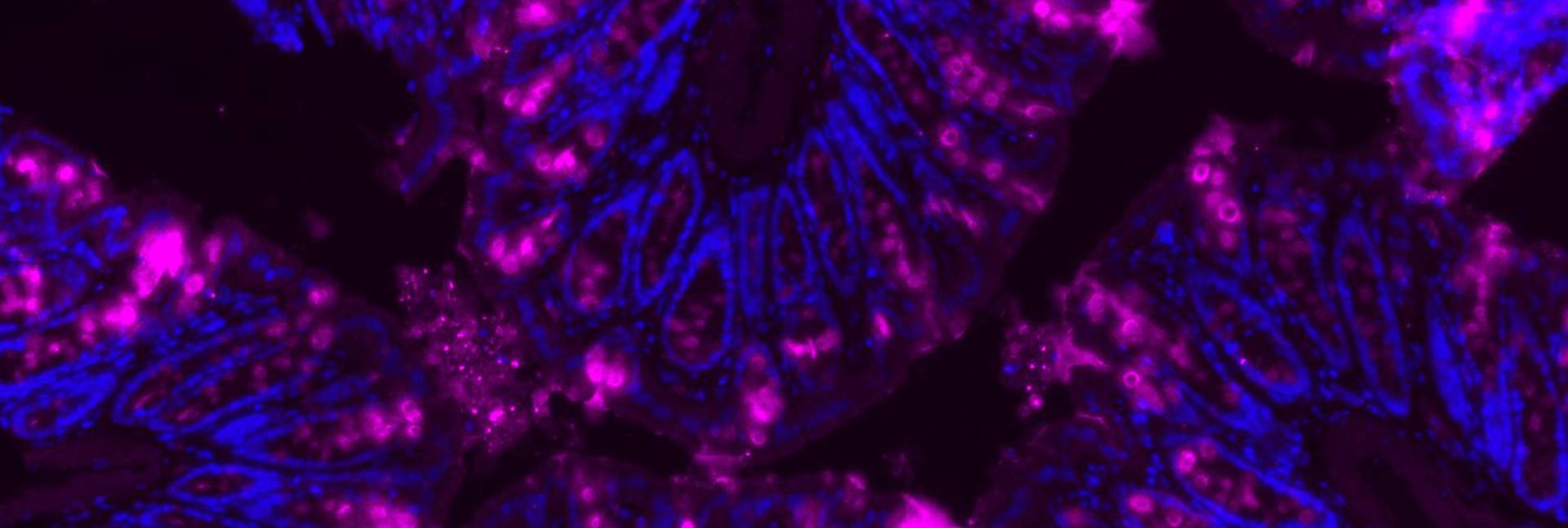

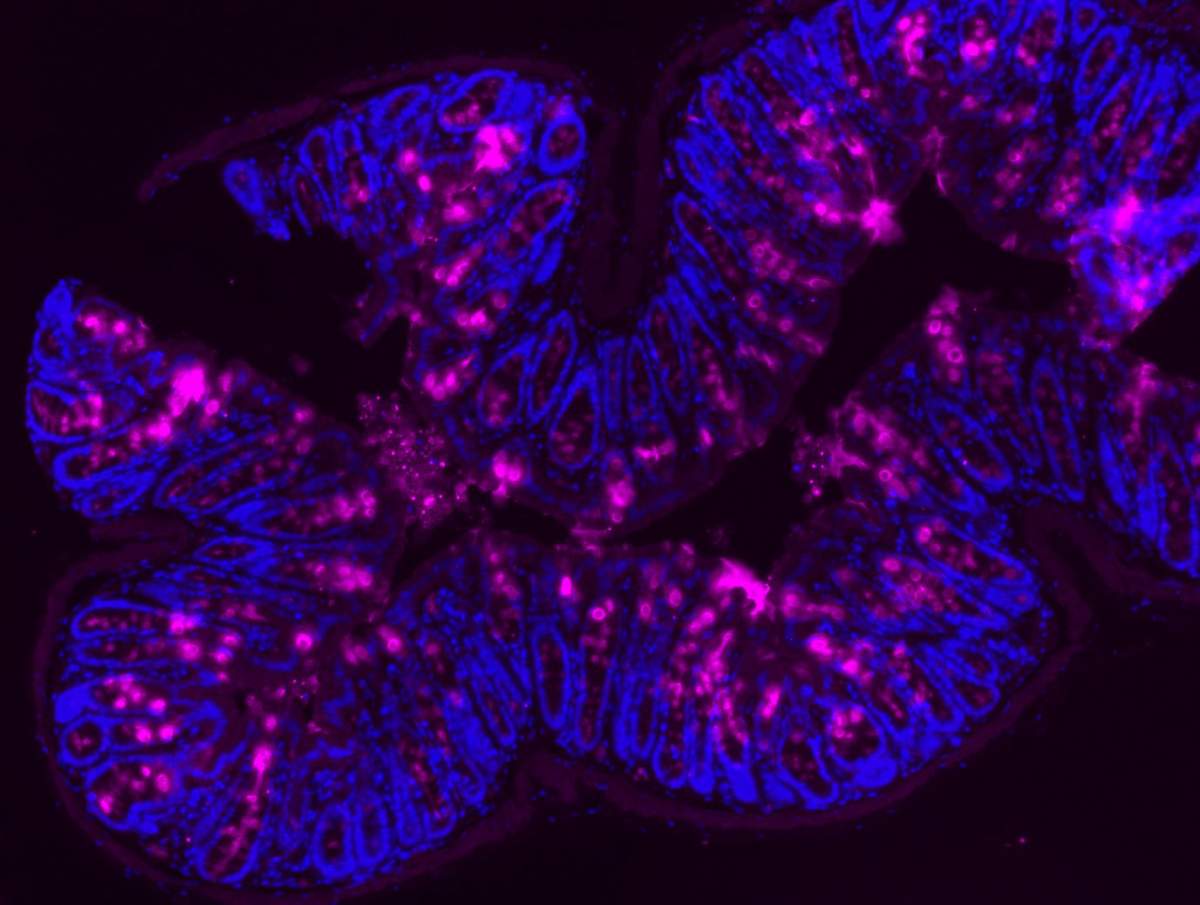

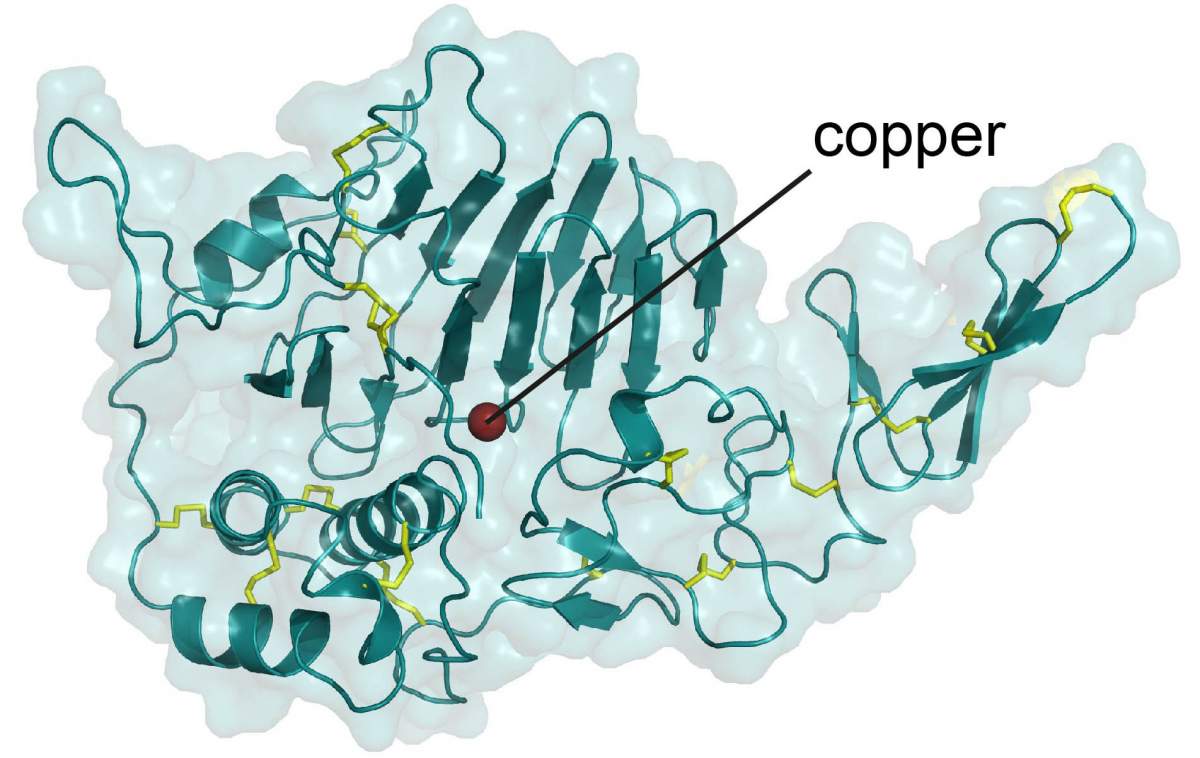

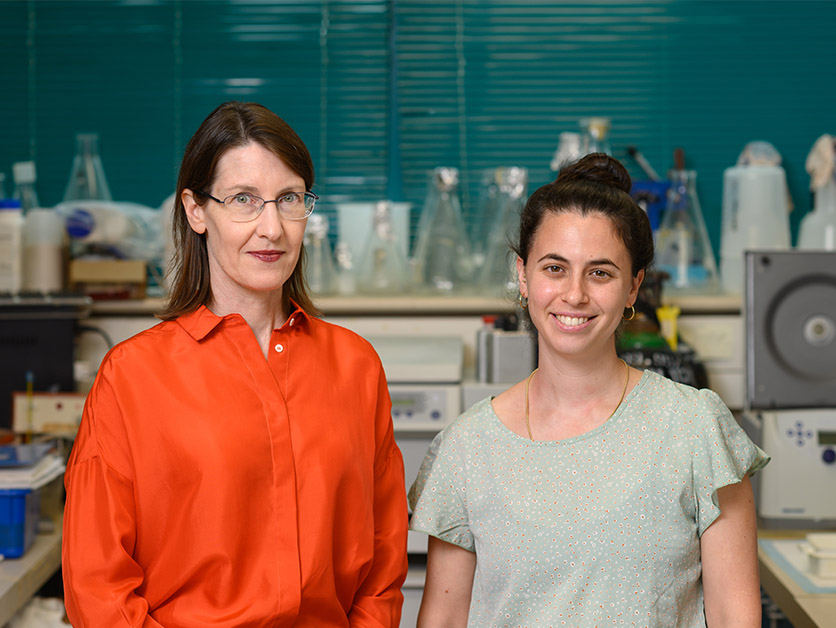

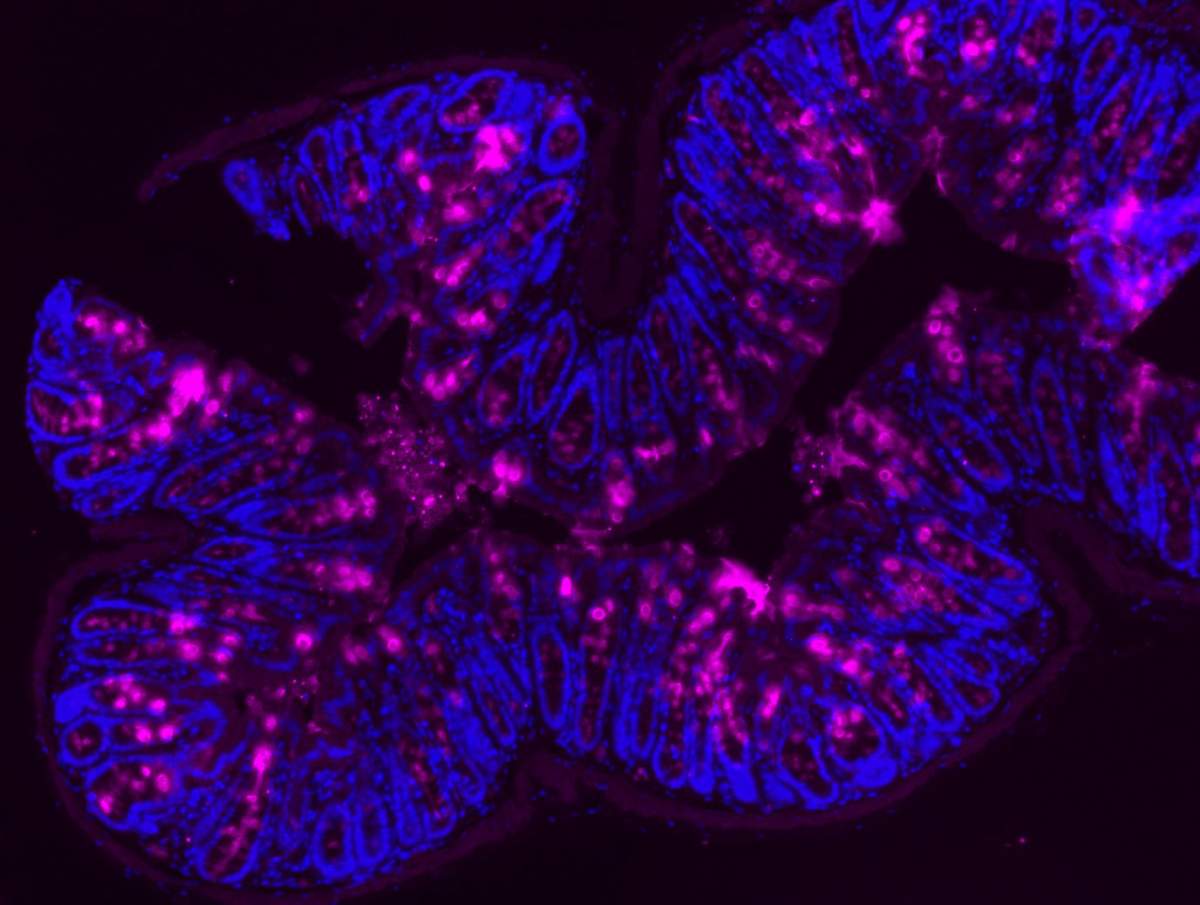

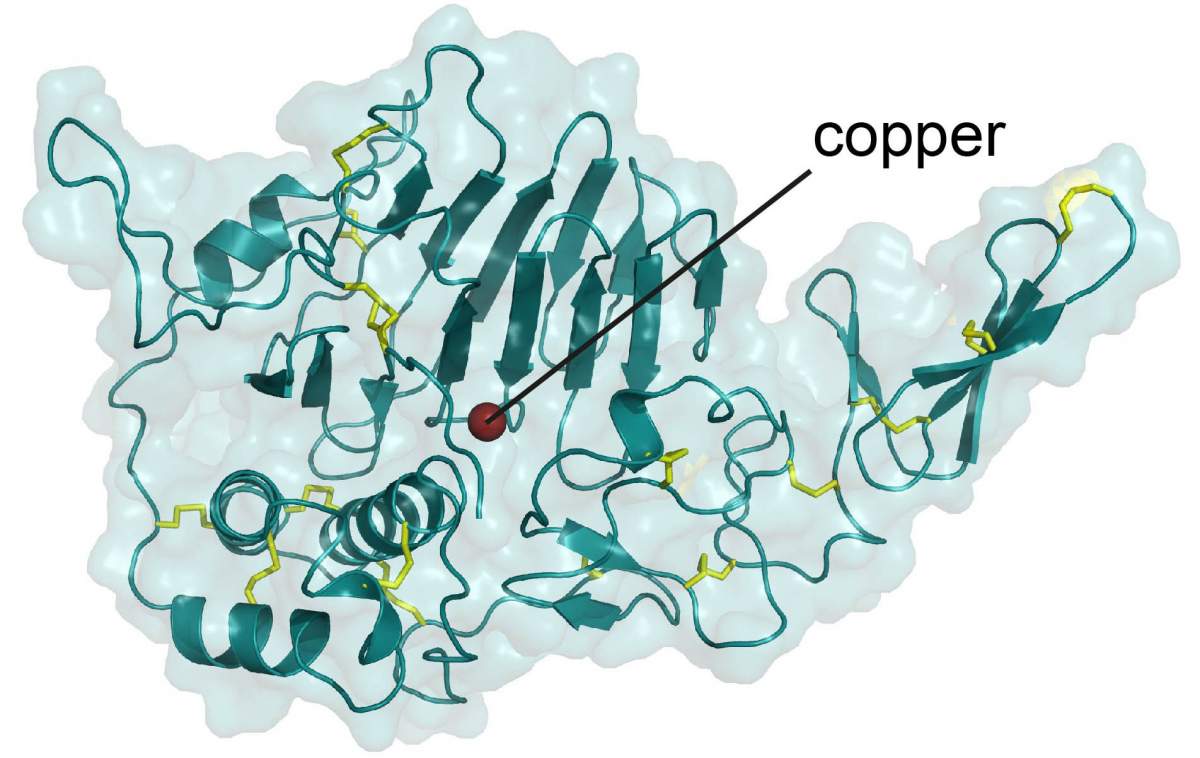

The team in Prof. Deborah Fass’s lab in Weizmann’s Chemical and Structural Biology Department embarked on a path that led to this discovery while mapping out the structure of a protein called mucin, a major component of mucus. The mapping was a formidable challenge, considering the gigantic size of the mucin molecules, which link together into even larger, net-like assemblies in ways that enable mucus to perform its diverse functions. Having managed to determine the structure of a large piece of a mucin molecule, the scientists observed something that seemed both familiar and out of place: a congregation of amino acids that looked a lot like a binding site for metal.

It was an intriguing find because it suggested previously unknown metabolic roles for mucus. The scientists threw ions of a variety of metals at the binding sites to see if anything would stick. Eventually, they concluded that the sites were meant to catch copper.

""The game the body has to play is moving copper from the diet to where it’s needed, without letting it make a mess along the way"

Present in shellfish, fish, nuts, seeds and dark chocolate, copper is less known for its nutritional value than some other trace metals, such as zinc and iron, but it is just as important to our bodies. Combined with various enzymes, it enables our cells to produce energy, contributes to the formation of connective tissue, facilitates the growth of new blood vessels and much more.

But copper can also be harmful. Copper ions are good at storing and transporting the electrons needed for biochemical reactions. Yet that same ability enables them to pass electrons to oxygen, generating reactive oxygen molecules that can damage cells.

“The game the body has to play is moving copper from the diet to where it’s needed, without letting it make a mess along the way,” Fass says. Her team performed a series of elegant experiments to see whether mucus helps the body do just that.

Sister, can you change a double for a single?

Nava Reznik, who led the study in Fass’s lab, crystallized a portion of the intestinal mucin molecule together with copper. This mucin, she discovered, had two binding sites – one for copper ions that have a double positive charge, which is the form that our body ingests in food, and another for copper ions with a single positive charge, the form that enters cells and whose extra electron has the potential to do good or ill.

The researchers hypothesized that intestinal mucin helps double-plus-charged copper ions pick up an electron, thus converting them into single-charged ions. Mucin then holds these single-charged ions in place, preventing them from releasing the newly acquired electrons in the wrong location. “Mucin doesn’t let that copper loose to run around and damage things,” Reznik says.

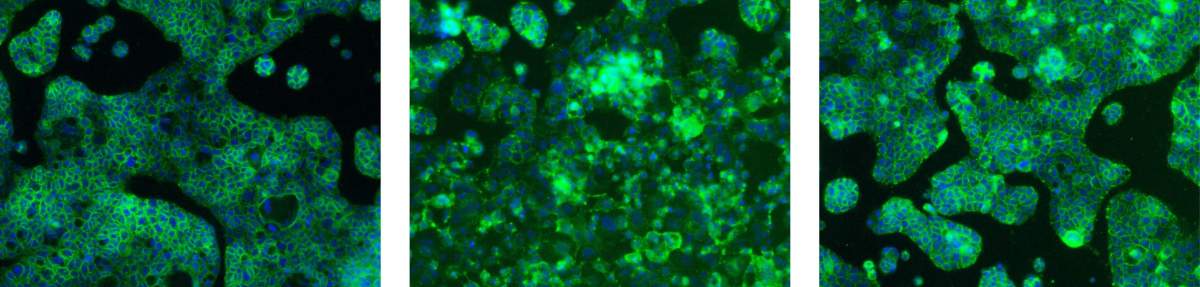

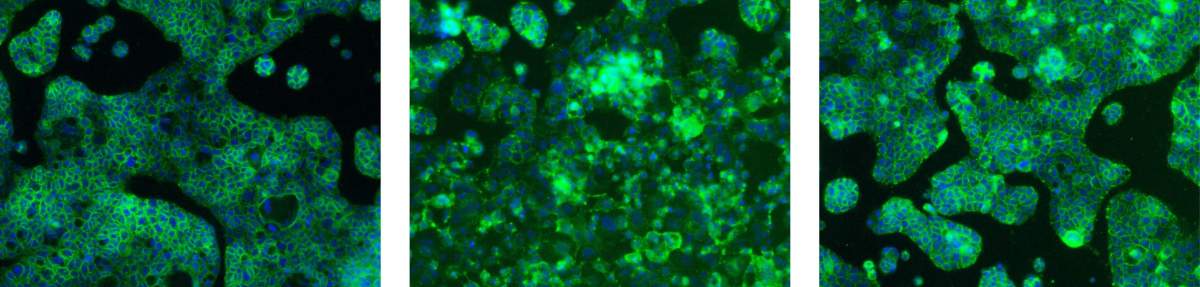

In experiments to test this hypothesis, the team showed that intestinal mucin stops the degradation of cells caused by exposure to copper, but it still allows copper-starved cells to safely take in copper ions and recover. The researchers conducted their experiments in laboratory dishes, but they believe the processes they revealed are the same as those that take place in the body, says Reznik.

The study’s findings suggest that intestinal mucin is a chaperone, a sort of assistant protein, for copper. Thanks to its two copper-binding sites, mucin ensures the proper behavior of this sometimes troublemaking metal. The researchers think the mucin chaperone might also be involved in delivering copper to the microbes in our gut, which also need this trace metal.

“It’s been well-known for decades that copper is chaperoned by proteins inside cells, but nobody thought to ask what happens to copper when you first ingest it,” Fass says.

No loose electrons get by the mucin chaperone

The study suggests that intestinal mucin might also prevent the squandering of antioxidants – beneficial molecules that have electrons to spare – by stopping electrons from flowing continuously from antioxidants to copper to oxygen. By holding on to single-charged copper ions, mucin seems to prevent this cycle.

Says Fass: “For example, what happens if you eat a copper-rich meal and drink orange juice, which contains vitamin C, an antioxidant? How do you prevent a flow of electrons from vitamin C and the resulting generation of reactive oxygen? Apparently, by holding on to single-charged copper ions at dedicated binding sites, the intestinal mucin blocks this flow.”

Indirect support for this explanation comes from the fact that in lung mucin, the team observed a binding site for only one form of copper – the one with double-positive charged copper ions. “We don’t breathe in vitamin C. Without this source of electrons, double-charged copper ions aren’t converted into single-charged ones, and there’s no need for lung mucin to control them,” Fass explains.

As new facts are being discovered about the under-studied – and, perhaps, under-celebrated – goo that lines our internal organs, the latest discovery by Fass’s team may inform other studies looking at mucus-chaperoned mechanisms, including in people with life-threatening metal deficiencies. “If we learn more about how copper crosses the mucus lining and gets absorbed by cells, we could perhaps develop better ways of directing copper molecules to tissues so as to help these patients,” Fass says.

Fass and Reznik got a fresh perspective during a recent scientific conference on copper metabolism, where they presented their study. Among the participants was a young boy severely disabled by copper deficiency, accompanied by a researcher who investigates the molecular mechanisms of his condition. “The conference showed how real copper metabolism issues are, not only in human physiology in general, but also in public health,” says Fass.