עיתונאיות ועיתונאים, הירשמו כאן להודעות לעיתונות שלנו

הירשמו לניוזלטר החודשי שלנו:

Dr. Yasha Gindikin was wide awake when the war began. His fear that Russia was about to invade Ukraine – which it did at around 5 a.m. on February 24, 2022 – had been keeping him up at night. Gindikin, a theoretical physicist then working at a research institute near Moscow, took the aggression as a personal tragedy. “My father’s parents came from Ukraine, but even without that, I couldn’t stand being part of this monstrous crime – giving it legitimacy by my very presence,” he recalls. He knew that continuing to voice protests against the war would land him in jail for years. His only plausible solution was to leave.

Gindikin would need to move himself, his pregnant wife and their two small children. He contacted three physicists in his field at universities across the United States, asking for help in finding a position outside of Russia. To his surprise, all three got back to him with the same advice: Check out the emergency program at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel.

The program was initially intended for Ukrainian scientists. It was initiated by Weizmann Institute Vice President Prof. Ziv Reich after hostilities broke out and was implemented by Dr. Igal Nevo, the vice president’s liaison for research affairs. Scientists fleeing the war were invited to be hosted by Weizmann labs; they were to be granted airfare, lodgings, financial support and laboratory space for three months. But draft-aged Ukrainian men were banned from leaving the country, thus hardly any scientists from Ukraine had applied.

“At the same time, refugees of a different kind were in dire need of a sanctuary,” says Prof. Sergei Yakovenko of Weizmann’s Mathematics Department. He was among the first to alert the Weizmann administration to the issue of the many Russian scientists who were rushing to leave their country after the war began.

""Walking down the hall of the physics building was like traveling through the pages of Science and Nature – so many offices had names of physicists whose papers I’d read and admired"

The Weizmann program was promptly expanded to include all scientists affected by the war in Ukraine, from both sides of the conflict. Soon applications from Russia started coming in. “Typically for Weizmann, there was very little bureaucracy,” says program coordinator Prof. Joel Sussman of the Chemical and Structural Biology Department, who helped to find a host lab for each applicant. “The response was amazing. Many scientists immediately agreed to serve as hosts, before they even knew that funding would be provided by the institute rather than their own budget.”

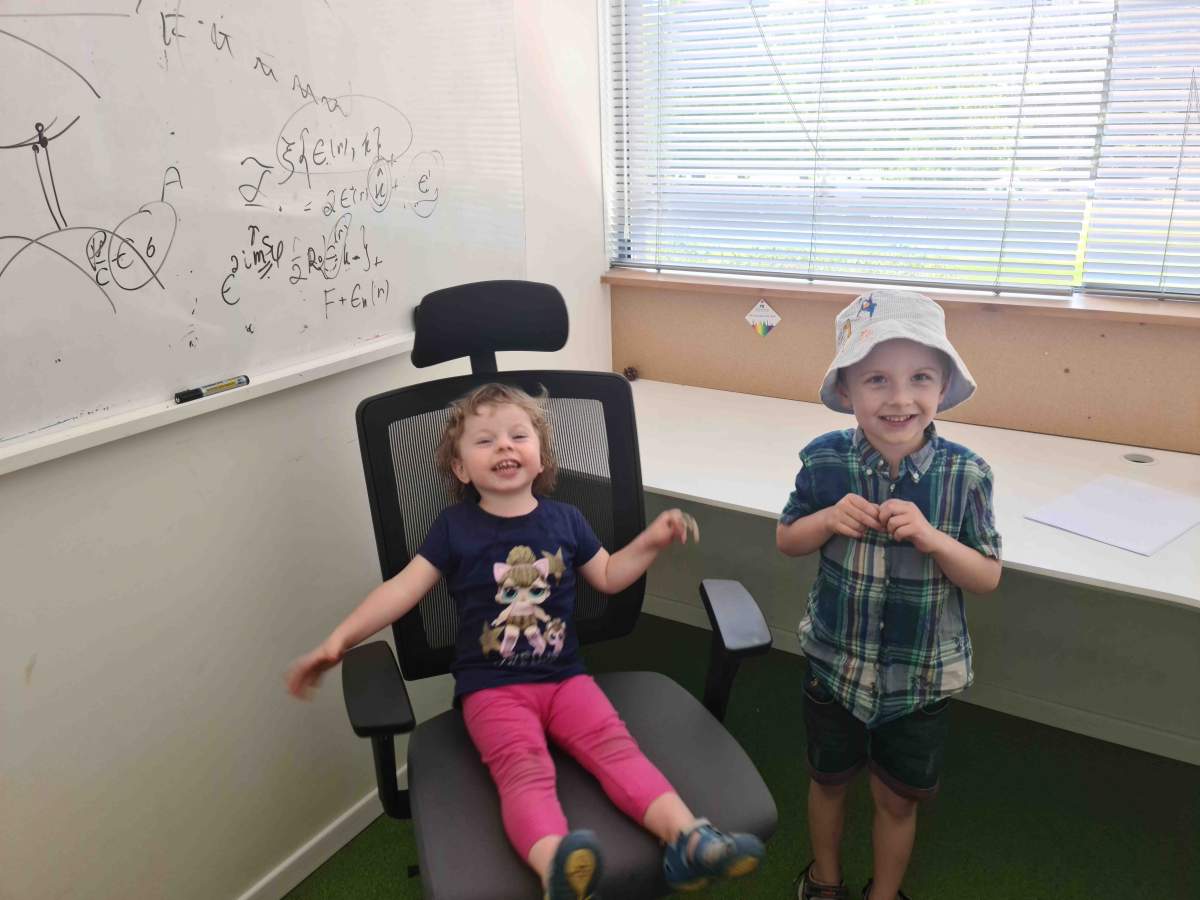

Gindikin was one of the first scientists to arrive. “When we came to Weizmann in early April, we learned that it was the end of Passover, a holiday of freedom,” he says. He describes his family’s arrival at Weizmann’s Kipnis Residences, in which program participants were lodged, as nothing short of a miracle. “We opened the door and saw an apartment full of boxes – to our amazement, they were filled with new dishes, blankets, sheets and all else we needed for a comfortable stay,” he recalls.

""The response was amazing. Many scientists immediately agreed to serve as hosts, before they even knew that funding would be provided by the institute rather than their own budget"

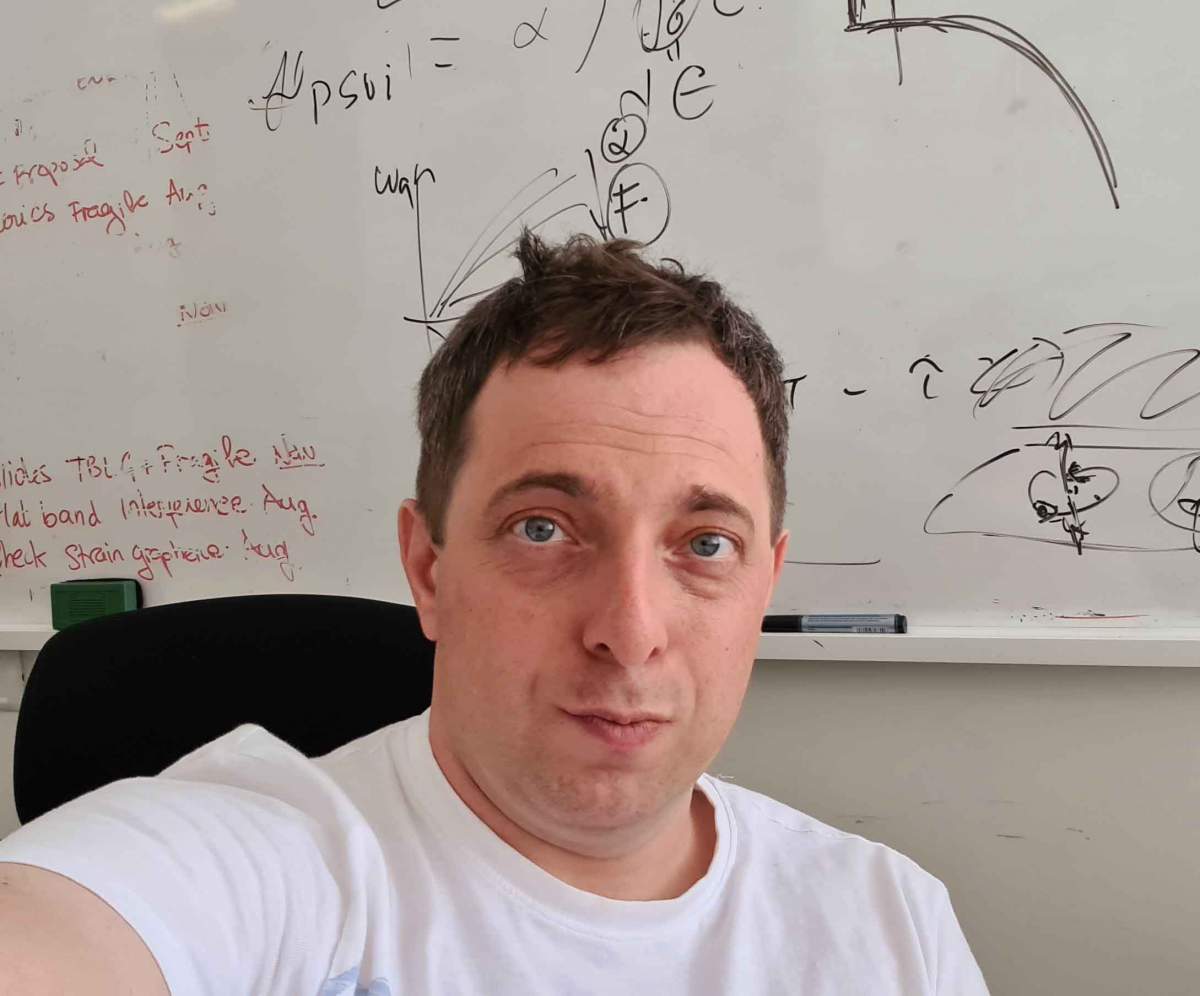

His sense of wonder continued when, after the holiday, he walked from the residence to the office of his host, Prof. Erez Berg of the Condensed Matter Physics Department. “It was a foggy morning, so the campus seemed like a dream. I hadn’t imagined to find an oasis full of blooming trees,” Gindikin says. “Then, walking down the hall of the physics building was like traveling through the pages of Science and Nature – so many offices had names of physicists whose papers I’d read and admired.” He was no less impressed by the bustling scientific atmosphere on campus, with conferences and almost daily seminars that continued through the summer.

In September 2022, Russia announced the mobilization of its army reservists, triggering a new exodus of people reluctant to take part in the fighting. The Weizmann administration responded by extending the emergency program until the end of March 2023.

Altogether, about 60 scientists took part in the program during the year it was offered. Most came from Russia, a few from Ukraine. Physicists made up the largest contingent, followed by mathematicians and computer scientists, as well as scientists working in the life sciences, chemistry and science teaching.

In parallel, Weizmann’s Feinberg Graduate School launched its own emergency initiative, playing host to some 20 students from Ukraine and Russia, who came to the campus for six months or longer, receiving airfare and full funding for their stay. About a third eventually remained at Feinberg as regular students; others went on to study elsewhere.

Other Israeli universities also opened their doors. Olga Orlova, editor-in-chief of T-invariant, a Russian-expat news website on science, politics and society, estimates that since the war began, some 800 to 900 researchers working in science, technology, engineering and mathematics moved to Israel from Russia and Ukraine, a substantial number for a country Israel’s size. Together with students, their number is estimated at nearly a thousand.

“Israel has a tradition of absorbing Jews, and now it went beyond that,” says Sussman, referring to the integration of Russian scientists in the country. Probably adding to the atmosphere of openness has been the fact that the scientific community in Israel, in contrast to many other countries, took no part in boycotting Russian science. “I believe it’s wrong to put the blame on scientists for decisions they didn’t make,” Sussman says.

The Weizmann emergency program served as a runway from which scientists could take off to longer-term positions. Gindikin was accepted as a postdoctoral fellow in the theoretical physics institute at the University of Minnesota. His stay at Weizmann was extended for an additional three months, until he received a US visa in October 2022, leaving Israel with his wife and three children, the youngest born in Beilinson Hospital.

Gindikin says he’ll always be grateful to all those who so wholeheartedly received him and his family at Weizmann. “We hadn’t expected such a warm welcome,” he says. “One particularly touching memory is of Departmental Secretary Inna Dombrovsky, who made sure we had all we needed for the new baby and brought our family food for an entire week after my wife came home from Beilinson.”

""The institute launched the program for purely humanitarian reasons, but it’s been a win-win move because we’ve gained some outstanding scientists who otherwise might not have come here"

While some of the other participants also moved on to positions abroad, yet others, particularly those eligible for aliyah under the Law of Return, looked for jobs in Israeli industry or academia. The Weizmann program provided them with crucial support while they waited for their Israeli citizenship applications to be approved.

About a dozen participants stayed on at Weizmann in various capacities. “The institute launched the emergency program for purely humanitarian reasons, but it’s been a win-win move because we’ve gained some outstanding scientists who otherwise might not have come here,” Sussman says.

One of these is prominent mathematician Prof. Victor Vasilyev, president of the Moscow Mathematical Society and a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences. “Vasilyev has revolutionized knot theory, one of the most enigmatic areas of topology – a branch of mathematics with a recently found relevance to quantum field theory,” Yakovenko says. “He discovered a virtually endless number of knot characteristics now named after him – Vasilyev invariants.” Vasilyev is now a visiting professor in the Mathematics Department.

Among the scientists who received positions at Weizmann is Tatiana Smirnova, a cell biologist who had specialized in microscopy. She quit her job at a gene biology institute in Moscow when the war started, devoting herself to helping Ukrainian refugees in Russia. She hosted refugees in transit in her Moscow apartment and served as a “car volunteer” – driving across Russia to transport refugees who couldn’t travel by train because they lacked foreign passports, or for other reasons. Once, she drove a Ukrainian family who couldn’t use public transport because they had four dogs.

In the fall of 2022, Smirnova went on the run herself, fleeing Russia with her two daughters and her draft-aged husband. She came to Weizmann through the emergency program, arriving in Rehovot with her family in December 2022. Her host, Dr. Yoseph Addadi, head of advanced optical microscopy in the Life Sciences Core Facilities Department, was so impressed with her knowledge and skills that he offered her a job in his unit.

Says Smirnova: “We wouldn’t have been able to come here if it weren’t for the Weizmann emergency program – it’s been a lighthouse in a stormy sea.”

Numerous Weizmann scientists and employees made important contributions to the running of the program, among them Dana Dvash and Taly Loebinger of the International Office and Housing Branch.