Failure to educate the young generation properly can have devastating consequences – not only among human beings, but among cells too. Uneducated immune cells, it turns out, might be at least partly responsible for the notorious flare-ups that occasionally occur in chronic inflammatory diseases of the digestive tract.

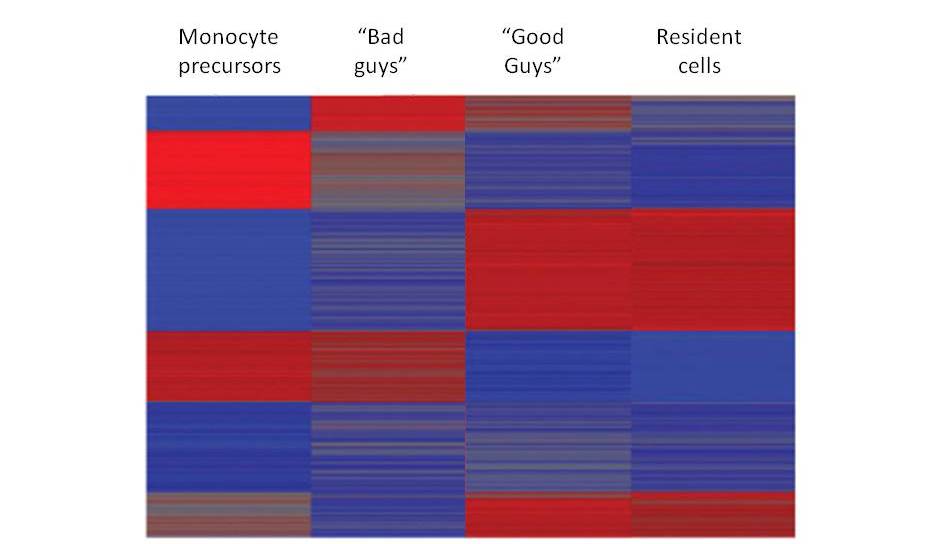

But if the gut lining is already inflamed – for example, as a result of bacterial infection – the newly arrived monocytes display a strikingly different behavior. Like teenagers giving in to peer pressure, these cells, on landing in a bad environment, turn bad themselves. They fail to undergo the proper education, so that their gene expression follows an abnormal pattern. As a result, instead of helping to maintain the gut, they start promoting inflammation, making it even worse than it was when they arrived.

Such misbehaving immune cells might help explain what happens during flare-ups of inflammatory bowel disease: Even a slight disruption resulting from exposure to bacteria or certain foods, which would normally be quickly corrected in a healthy person, leads to lasting inflammation. And once such inflammation is in place, the newly arriving monocytes, acting like juvenile delinquents who refuse to be educated, apparently keep aggravating this inflammation instead of correcting it.

The study, reported recently in

Immunity, was led by

Prof. Steffen Jung of the Weizmann Institute’s Immunology Department and performed in transgenic mice developed in his laboratory. The research was conducted by Dr. Ehud Zigmond, a physician and Ph.D. student, and Dr. Chen Varol of the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, in collaboration with departmental colleagues

Dr. Guy Shakhar and Julia Farache, as well as Dr. Gilgi Friedlander of Biological Services. Reagents were provided by Dr. Kenneth M. Murphy of Washington University School of Medicine, Dr. Matthias Mack of the University of Regensburg in Germany, Dr. Nahum Shpigel of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Dr. Ivo G. Boneca of the Pasteur Institute and INSERM in France.

The findings point to new ways of treating inflammatory bowel disease. One approach would be to temporarily interrupt the recruitment of new monocytes to the gut once inflammation has begun, to prevent its further aggravation. In their studies in mice, Jung and his team indeed showed that antibodies blocking the arrival of new monocytes to the colon alleviated the symptoms of inflammation.

But in the longer term, as in many other areas of life, it is education that holds the real promise for the future. Once scientists understand in greater detail how monocyte education takes place in the gut lining, they should be able to ensure that it runs its proper course, so that the monocyte “kids” behave themselves, contributing to health rather than disease.

Prof.Steffen Jung’s research is supported by the Jeanne and Joseph Nissim Foundation for Life Sciences Research; the Leir Charitable Foundations; the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust; the Adelis Foundation; Lord David Alliance, CBE; the Wolfson Family Charitable Trust; the estate of Olga Klein Astrachan; and the estate of Florence Cuevas.

Dr. Guy Shakhar’s research is supported by the Clore Center for Biological Physics; the Yeda-Sela Center for Basic Research; the Jeanne and Joseph Nissim Foundation for Life Sciences Research; the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust; the Dr. Dvora and Haim Teitelbaum Endowment Fund; Simone Pastor, Monaco; Lord David Alliance, CBE; Paul and Tina Gardner, Austin, TX; the Steven and Beverly Rubenstein Charitable Foundation; and the Paul Sparr Foundation.