עיתונאיות ועיתונאים, הירשמו כאן להודעות לעיתונות שלנו

הירשמו לניוזלטר החודשי שלנו:

“In my early years as a chemistry student,” says Dr. Sidney Cohen of the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Faculty of Chemistry, “the existence of atoms and molecules was taken on faith: We mostly relied on indirect evidence through spectroscopy or other highly specialized, generally inaccessible techniques. No one had ever seen a molecule, certainly not its internal structure. Today, we can see atoms and molecules regularly on readily available instrumentation. That is really an amazing development in the field.”

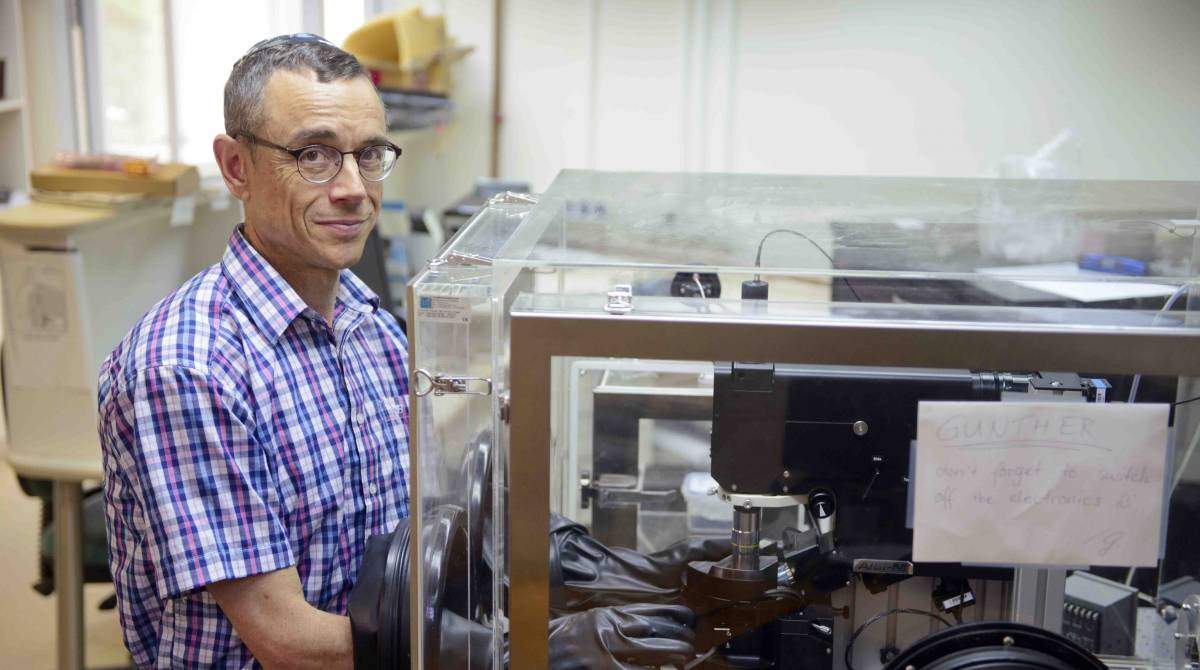

Cohen completed his doctoral studies at the Weizmann Institute under the guidance of Prof. Ron Naaman. During his postdoctoral research at the IBM Research Center in the US, Cohen learned atomic force microscopy (AFM), which was a brand new field at the time. When he returned to the Weizmann Institute of Science in 1990, he established the first AFM lab in Israel. “This is the instrument that enabled the field of nanotechnology to be developed,” he says. “For molecules, we can study their structure, mechanics or electrical properties; or we can move them around to design new, molecular-based devices. The AFM is designed for a field that is constantly advancing: It can work in any environment, for research on samples in liquid, vacuum or other lab conditions, and it can be used to investigate all types of materials—soft, hard, conductors or insulators.”

Today, we can see atoms and molecules regularly

Visiting groups of students and teachers are not an uncommon sight in the Surface Analysis Unit that Cohen heads in the Institute’s Chemical Research Support Department. Cohen began working with the Institute’s Science Teaching Department early on, developing teaching units for middle and high school students.

Learning nanoscience online

Lately, Cohen has been working with Prof. Ron Blonder of the Science Teaching Department on a new project, EduNano, which they are undertaking in collaboration with academic and industrial partners in Israel and Europe. The idea behind this project is to build an online nanoscience curriculum that can answer the needs of undergraduate and graduate students seeking credit, as well as teachers and those working in the high-tech industry who want to stay abreast of the newest technologies. Each participating academic institution – five in Israel and three in Europe – contributes two online courses to the project. The curriculum is developed using input from workers in high tech; thus helping to design courses that will meet future nanotechnology needs.

In the 20 years that Cohen has been teaching at the Weizmann Institute, he has seen teaching methods undergo many changes: “I once taught using chalk on a board. Then I moved up to hand-written overhead transparencies, and these were replaced by computer presentations. Each was really a pedagogical change that required designing new teaching practices,” he says. “Online courses are a new leap. When I lecture in the classroom, I get a sense from the students of what they have understood. When I lecture to the camera and microphone on my laptop, a certain interest and excitement is lost. I miss lecturing to that room of students, but this experience can be replaced by forums, chats and other electronic tools.”

Cohen points out that educators today face a huge challenge: “Google has replaced textbooks; electronic books have replaced paper ones. How does one use the new technology to improve education? Social media can, for example, help students who did not understand a lecture the first time, or it can help create positive connections among students and between teachers and students.”

During this first year, students throughout Israel, including 20 Weizmann Institute of Science graduate students and a number of Europeans, have already completed EduNano courses, and an expansion of the project is now being planned.