עיתונאיות ועיתונאים, הירשמו כאן להודעות לעיתונות שלנו

הירשמו לניוזלטר החודשי שלנו:

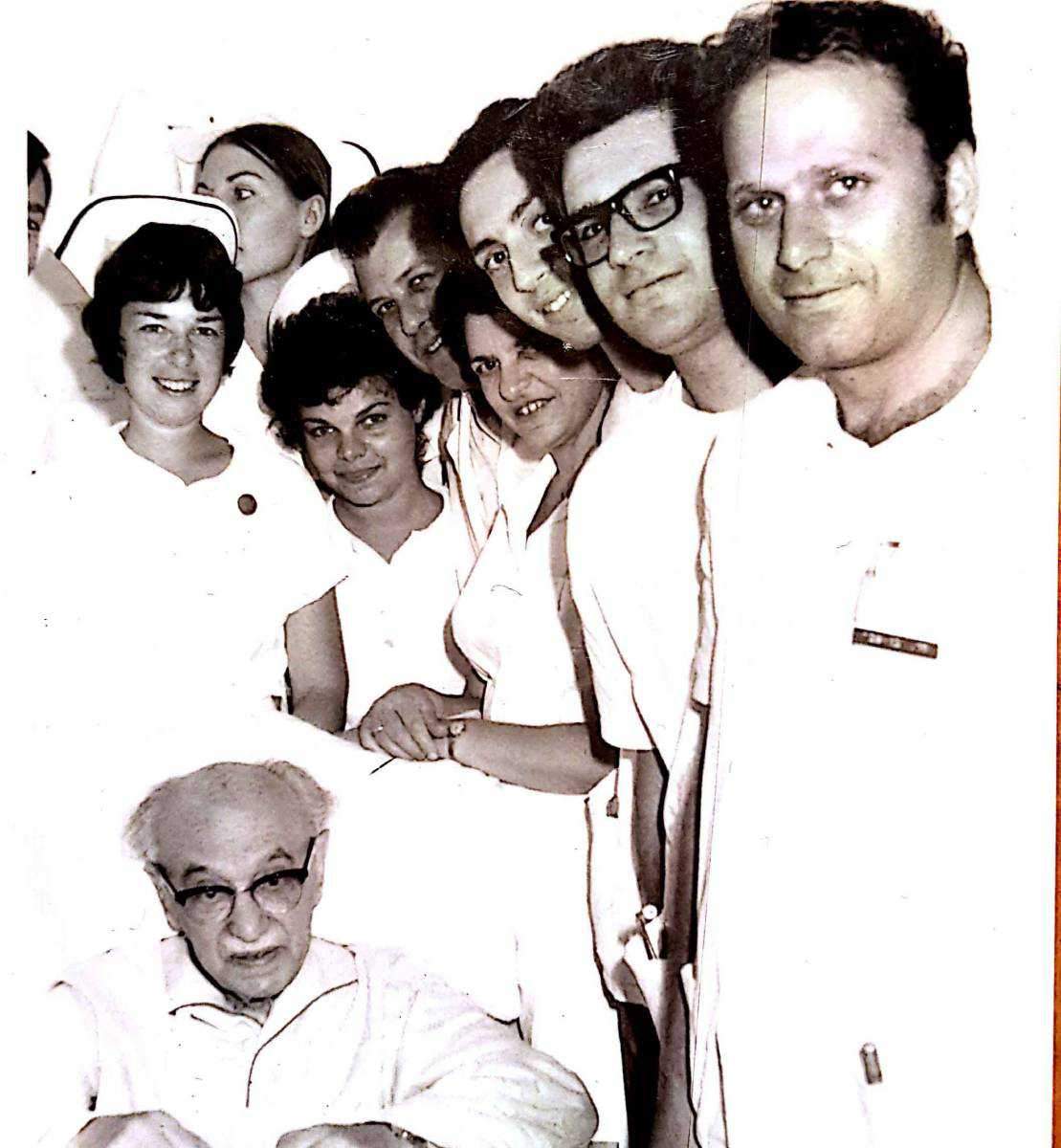

Long before Weizmann Institute scientists and others discovered the beneficial side of our internal bacteria – our microbiome – Dr. Silvio Pitlik had his misgivings about administering large quantities of anti-bacterial drugs. Pitlik was a doctor in the internal medicine department of Beilinson Hospital for 43 years – a number of those years as head of the department – and in that time he observed something like 100,000 cases in which antibiotics were given. “In my opinion,” he says, “that was unnecessary in something like 80% of the cases. Most of the patients would have recovered without them.” Pitlik, 71, has since retired from the hospital and joined the Weizmann Institute as a visiting scientist in the lab of Prof. Rotem Sorek of the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Molecular Genetics Department.

Calling antibiotics an “atom bomb for the microbiome,” Pitlik points to numerous studies suggesting that these “wonder drugs have a down side, including an increased risk of Crohn’s disease and obesity. They simply wipe out all the bacteria in the body – harmful and friendly. Our microbiome is like an ecosystem: It needs diversity to function properly. If, for example,” he says,” we wipe out the animal that spreads seeds in the forest and fertilizes the ground, we can lose the whole forest. Harming our internal ecosystem can have similar, disastrous results.”

Resistant bacteria might even have some advantages that we are not yet aware of

Pitlik practices what he preaches: His family never received antibiotics. Of course he is not against giving antibiotics when they are truly needed: In such life-or-death situations as bacterial meningitis or highly contagious infections the benefits outweigh the disadvantages. On the other hand, he continues, “antibiotic resistance is not the future apocalypse that some have predicted. If it were, the dead would already be lining the streets. Resistant bacteria might even have some advantages that we are not yet aware of.”

Born in Argentina, Pitlik “breathed Zionism at home from age zero,” he says. Pitlik taught himself to read at age two, and he read Hebrew – reading about the War of Independence and the establishment of the State of Israel – in the Davar daily paper. He graduated from high school at age 15, finished medical school six years later and, after a stint in the Argentinian army, made Aliyah to Israel at age 24.

“Twelve days after my arrival in Israel, I was working in the internal medicine department of Beilinson Hospital,” Pitlik says. He remained in the department for another 43 years; besides serving as head of the department, Pitlik served two terms as Chair of the Israeli Society for Infectious Diseases.

It was at a lecture that Sorek had given to members of the Society that Pitlik and Sorek met. The two started discussing the topic of the lecture, and this eventually led to the idea of Pitlik joining Sorek’s lab. “I showed up at the lab the day after I retired from the hospital,” he says, adding with a smile: “I don’t believe in holidays or resting.”

In Sorek’s lab, Pitlik reviews research papers and gives lectures to the group. “The students are the real assets of this place,” he says. “They give me the energy that only young people can give, and I feel young, thanks to them. Maybe it is their ‘good bacteria,’ that I’m feeling!”