עיתונאיות ועיתונאים, הירשמו כאן להודעות לעיתונות שלנו

הירשמו לניוזלטר החודשי שלנו:

Obesity and diabetes continue to top the charts of current health threats. More than two billion people are affected worldwide, and more than three million deaths each year are linked to complications associated with obesity. The detrimental effects of obesity and diabetes are often not caused by the excess weight itself, but by side effects of obesity that dramatically increase susceptibility to inflammation and infection. Overweight and obese individuals are at enhanced risk of contracting microbial infections, and they frequently develop inflammatory complications − for example, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or blood vessel inflammation that leads to atherosclerosis and heart disease. Understanding how obesity causes these dangerous side effects and turns into a devastating, potentially life-threatening disease is critical to preventing the untimely death of obese individuals. However, very little is known about the molecular details of the events that link chronic obesity to inflammation and infection, thus hampering the development of preventive and therapeutic strategies.

The team of Prof. Eran Elinav in the Weizmann Institute of Science’s Immunology Department found an unexpected explanation for this phenomenon. In a study published in Science, Elinav and his colleagues used mouse models of metabolic disease to study the connection between obesity and elevated risk of infection. They found that obese mice not only showed a dramatic accumulation of bacterial products in their blood and inner organs, but were also extremely susceptible to oral infection with pathogenic bacteria. But the twist to the story appeared when the scientists put the obese mice on a weight-reduction diet: The susceptibility to severe infection remained. This demonstrated that adiposity itself was not the cause for this life-threatening complication. Rather, Elinav’s team found that high blood sugar levels were the decisive factor that enabled bacteria living in the gut to invade the bloodstream and cause severe infection.

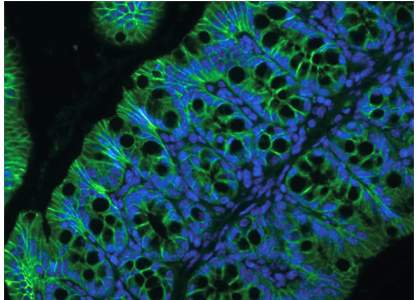

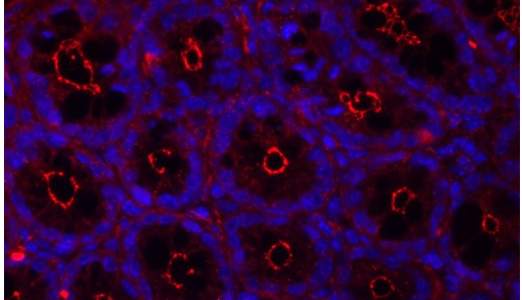

In a healthy individual, blood sugar levels are usually kept within a very narrow range by multiple control mechanisms of the body. In contrast, such metabolic diseases as obesity and diabetes are frequently accompanied by chronically elevated blood sugar levels. Dr. Christoph Thaiss, a postdoc in Elinav’s lab who led the study, investigated the mechanism by which elevated blood sugar levels led to the highly enhanced risk for infection. He found that high levels of sugar in the blood stream distort the function of intestinal epithelial cells. This type of cell lines the gastrointestinal tract and forms a thin barrier between the body and the inside of the gut, which is colonized by a vast amount of commensal bacteria. The gut epithelial cells thus have the complicated task of allowing food particles to enter the body while keeping potentially harmful bacteria corralled in the gut. Using an advanced technology developed together with the team of Prof. Benjamin Geiger, also of Weizmann Institute of Science, the researchers were able to show that high levels of sugar are “sensed” by these gut epithelial cells, leading to profound changes in their gene expression and alteration in the critical function of maintaining a tight barrier between the body and the inside of the gut. Thaiss and his colleagues discovered that in the scenario of obesity and diabetes, high sugar levels cause the snug contact between intestinal epithelial cells to become permeable, allowing gut-resident bacteria and their products to enter the blood stream, with detrimental consequences for health.

Elinav’s team also looked at the connection between high blood sugar level and microbial invasion in humans. They recruited a cohort of volunteers for blood testing that included an analysis of blood sugar levels and the presence of bacterial molecules. Similar to the team’s findings in mice, there was a strong correlation between chronically elevated sugar levels and bacterial products in the blood. In contrast, there was no correlation between the signs of bacterial presence and body weight or adiposity, demonstrating that for gut permeability excess weight mattered much less than high blood sugar levels.

This study provides a possible answer to the question of why obesity is so frequently accompanied by an enhanced risk of severe infection. It also suggests that strategies to tightly control blood sugar levels may prove effective in preventing many of the harmful side effects of obesity. Thaiss, Elinav and their colleagues suggest that the molecular explanations they found in this study could contribute to a better understanding of other diseases that have been linked to gut barrier defects, such as chronic liver inflammation, food allergies and other conditions.