Waste management is a big issue anywhere, but at the cellular level it can be a matter of life and death. A Weizmann Institute study, published in the Journal of Cell Biology, has revealed what causes a molecular waste container in the cell to overflow in Batten disease, a rare but fatal neurodegenerative disorder that begins in childhood. The findings may form the basis for a therapy for this disorder.

The research was conducted in the laboratory of

Prof. Jeffrey Gerst of the Molecular Genetics Department by Rachel Kama and postdoctoral fellow Dr. Vydehi Kanneganti, in collaboration with Prof. Christian Ungermann of the University of Osnabrueck in Germany. All the studies were performed in yeast: The yeast equivalent of the mammalian CLN3 gene has been conserved almost intact in the course of evolution, making them an ideal model for study. In fact, so similar are the yeast and the mammalian genes that when the researchers replaced a missing copy of the yeast gene with a working copy of mammalian CLN3, normal functioning of the yeast cell was restored.

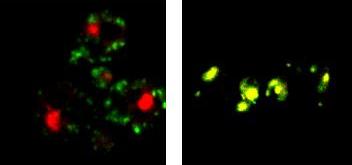

The experiments showed that the yeast equivalent of CLN3 is involved in moving proteins around in the cell – the scientific term is “protein trafficking.” The gene activates an enzyme of the kinase family, which, in turn, launches a series of molecular events regulating the trafficking. When the yeast CLN3 is mutated, this trafficking is disrupted. As a result, certain proteins accumulate abnormally in the lysosome, the cell’s waste-recycling machine, instead of being transported to another destination. At some point the lysosome is filled beyond capacity; it then interferes with molecular signaling and other vital processes in the neuron, eventually killing the cell.

A great deal of research must still be performed before this finding can benefit humans, but the clarification of the CLN3 function is precisely what might help develop a new therapy. Replacing the defective CLN3 in all the brain’s neurons would be a daunting challenge; but replacing its function – for example, by activating the relevant kinase by means of a drug – should be much more feasible.

Prof. Jeffrey Gerst’s research is supported by the Miles and Kelly Nadal and Family Laboratory for Research in Molecular Genetics; the Hugo and Valerie Ramniceanu Foundation; the Y. Leon Benoziyo Institute for Molecular Medicine; the Yeda-Sela Center for Basic Research; the estate of Raymond Lapon; the National Contest for Life (NCL) Stiftung, Germany; and the Israel Science Foundation, Israel. Prof. Gerst is the incumbent of the Besen-Brender Professorial Chair of Microbiology and Parasitology.