In the early 1930s, Dr. Bloch was a young physicist in Brussels. Behind him was a lengthy journey across Europe. He was born in April 1900 in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in the Galician town of Delatyn where he spent his childhood, the youngest of nine children in a traditional Jewish family. He studied physics at Prague’s German University and worked, during his student days and afterwards, as a journalist in the German-language newspaper Prager Tagblatt. Upon completing his studies with honors, he stayed on at the university as a research assistant. Several years later he moved to Belgium, as a senior researcher in the chemical physics department of the Brussels’ Université Libre, in the area of infrared spectroscopy.

During that time, Dr. Chaim Weizmann was planning to establish a physics department in the Sieff Institute he had founded in Eretz-Israel. In the summer of 1934, he invited Benjamin Bloch to come over and take this mission upon himself. Bloch welcomed the offer as an opportunity to combine Zionism with science. He initially joined Dr. Weizmann’s team in London, then in the fall of 1935 arrived in Rehovot with his wife Bronia, an ophthalmologist, and their baby daughter Rivka. In Eretz-Israel, the couple would give birth to two more daughters, the twins Navah and Naomi.

As there was a delay in the establishment of the physics department, Dr. Bloch started helping Weizmann in managing the Institute (a challenging task, in view of budgetary difficulties and research requirements). He revealed such talents in this area that, in 1936, Dr. Weizmann asked Bloch to continue working with him in the management of the Institute. Bloch accepted the offer; he was to fill this position with great success for nearly 25 years.

Even though Bloch, then 36, was much younger than Weizmann, the two became close friends. Dr. Vera Weizmann, Chaim Weizmann’s wife, wrote years later: “My husband had full trust in Dr. Bloch, in his fairness and integrity. Dr. Bloch, for his part, was a loyal friend of my husband’s, fulfilling his work with faith and precision.”

Dr. Bloch missed physics a great deal and mourned its loss. He occasionally told his family and friends, referring to the loss of his siblings in the Holocaust: “I used to have a brother and seven sisters – but no more; I used to have my physics – but no more.” Nevertheless, says his daughter Navah: “I recall Felix Bloch (no relation), the Nobel laureate in physics who was a friend of my father’s, saying that in terms of personal fulfillment, he would have gladly changed places with my father.”

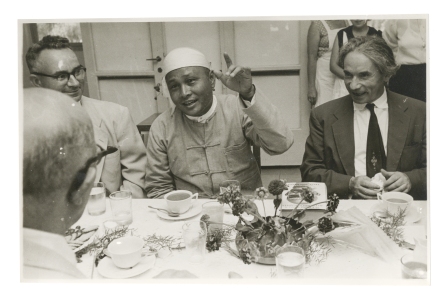

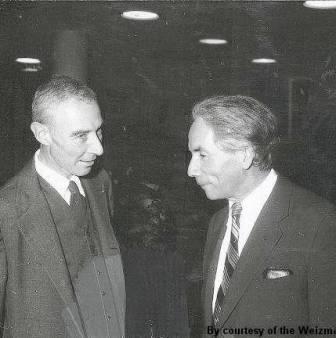

During World War II, when Dr. Weizmann spent much time in London, Bloch assumed even greater managerial responsibilities. With the inauguration of the Weizmann Institute in 1949, he was appointed its administrative director. The Institute’s scientists and staff admired and respected him not only as a manager but as a human being. In 1952, at a meeting of the Board of Directors of the American Committee for the Weizmann Institute in New York, Meyer Weisgal, then Chairman of the Institute’s Executive Council, proposed to express special thanks “to Dr. Bloch, who has been the conscience of the Institute since 1934. He has had to grapple with enormous problems in his daily administration; he has had heartaches and difficulties in dealing with a staff of 300 people, and scientists could sometimes be as temperamental as artists. Yet the Institute is one of the very few public institutions in Israel which in the 18 or 19 years of its existence has never had a strike.” On other occasions, Institute scientists Aharon Katzir and Amos de-Shalit, as well as many others, lavished praise on Bloch, expressing their appreciation for his commitment to the Institute, as well as for his contribution to the Institute’s strength. Bloch and his wife hosted in their home numerous high-ranking guests of the Institute, among them the physicists Robert Oppenheimer and Niels Bohr.

In addition to his managerial responsibilities at the Institute, Dr. Bloch contributed a great deal to numerous emerging organizations of the young State of Israel. He was a board member of Magen David Adom (Israel's emergency medical service) and of the Israel Maritime League; as a representative of the Institute, he served on national scientific councils before and after the establishment of Israel. During World War II, he was active in the national defense committee and in the Haganah. His daughter Navah recalls that he used to tell her and her sisters: “We are building a country, we are building industry.” In the summer of 1955, Bloch represented Israel at a session on the peaceful uses of atomic energy, organized by the USSR Academy of Sciences in Moscow. At the session he spoke in Russian – one of the many languages he knew.

In his late fifties, Dr. Bloch had plans to return to physics but, sadly, he fell ill. He went for treatment to the United States but passed away in a New York hospital in April of 1959, just one day before the celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Institute, to which he had devoted such a significant part of his life. He was buried in Rehovot. Thousands took part in the funeral: When the funeral procession left the Weizmann Institute, Rehovot residents lined both sides of the road; as the procession passed the police station, the policemen saluted Dr. Bloch on his final journey.

At the Weizmann Institute, Dr. Bloch has been commemorated in a variety of ways: Student scholarships have been created in his name and a room in the physics building was named after him (it is scheduled to be re-dedicated in the near future). But most prominent, of course, is the lovely tree-lined road that leads from the Institute’s historic entrance to the heart of the campus: Benjamin Bloch Avenue.

Special thanks to Navah Bloch Rodrig and to the Weizmann Institute Archives for help in the preparation of this article.