עיתונאיות ועיתונאים, הירשמו כאן להודעות לעיתונות שלנו

הירשמו לניוזלטר החודשי שלנו:

The two sides of the human body are not created equal. The left and right hemispheres of the brain perform different functions; the heart is located off ce nter to the left; and various other internal organs have their respective locations on either side of the abdomen. How this asymmetry arises during fetal development is not yet fully understood, but a directional “compass” exists already at the level of individual cells: A new study headed by Weizmann Institute researchers has revealed that cells can “tell” left from right. The results of this study appeared in Nature Cell Biology.

nter to the left; and various other internal organs have their respective locations on either side of the abdomen. How this asymmetry arises during fetal development is not yet fully understood, but a directional “compass” exists already at the level of individual cells: A new study headed by Weizmann Institute researchers has revealed that cells can “tell” left from right. The results of this study appeared in Nature Cell Biology.

A team of scientists headed by Prof. Alexander Bershadsky, who is at both the Weizmann Institute and the the National University of Singapore (see below), explored the self-organization of the cytoskeleton, the network of tiny protein fibers that holds the cell together. Its name notwithstanding, this “skeleton” is far from rigid or static. On the contrary, it continuously alters its shape when the cell, after undergoing division, becomes attached to the surrounding matrix. These alterations crucially affect the formation of the cellular points of contact, or adhesion, which, in turn, play an important role in the cell’s motion and in its communication with its surroundings.

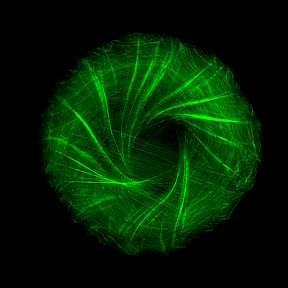

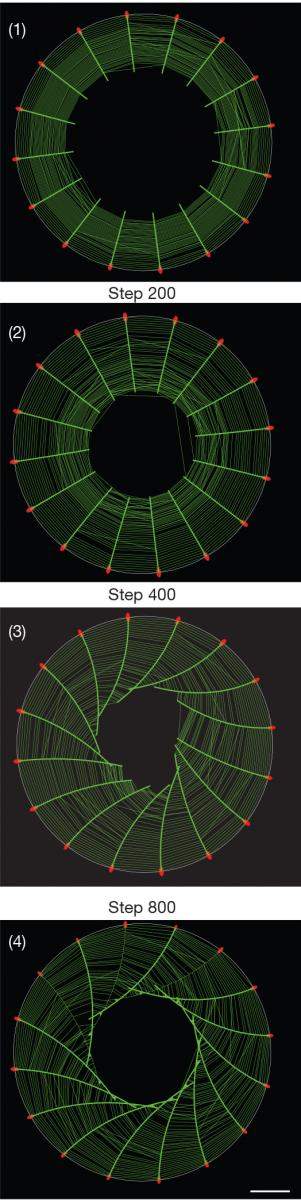

To observe how the cytoskeleton organizes itself when such points of adhesion are created, Dr. Yee Han Tee and other members of Prof. Bershadsky’s team in the Mechanobiology Institute in Singapore, used a clever approach that eliminated the disturbances resulting from cellular motion and enabled them to clearly visualize the cytoskeleton within individual cells: They caused cells to stick to miniature circular discs, each the size of one cell – that is, measuring less than one-twentieth of a millimeter across. Labeling the fibers of actin, the major protein component of the cytoskeleton, with green fluorescence, the scientists then observed bundles of these fibers growing from the edges of the cell toward its center, forming a “radial” pattern – one resembling the spokes of a wheel.

The big surprise came when the scientists played a time-lapse video of the process, collapsing twelve hours into a few minutes. They saw that the symmetry of the actin “spokes” was always broken in the same direction, so that all the fibers tilted to one side, causing the emerging cytoskeleton to swirl counter-clockwise and ultimately creating a helical structure.

The big surprise came when the scientists played a time-lapse video of the process, collapsing twelve hours into a few minutes. They saw that the symmetry of the actin “spokes” was always broken in the same direction, so that all the fibers tilted to one side, causing the emerging cytoskeleton to swirl counter-clockwise and ultimately creating a helical structure.

To explain how and why the swirling occurs, Prof. Tom Shemesh, then a postdoctoral fellow at Weizmann and now at the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, together with Prof. Michael Kozlov of Tel Aviv University, built a mathematical model that incorporated the mechanical parameters of the actin fibers and the forces exerted on them during the formation of the cytoskeleton, as measured in the study. Taking part in the study were also scientists from the University of Michigan and from the Sanford Burnham Medical Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

The model correctly predicted the dynamics of the cytoskeleton formation and revealed that the swirling observed in the experiment resulted from the interaction between two types of fibers that crisscross one another in a perpendicular fashion, as in a spider’s web. The sturdier radial actin fibers grow from adhesion points at the cell’s edges toward its center. Running perpendicular to them and parallel to the cell’s boundary are the force-generating actin fibers that contain an additional protein, myosin. This protein is responsible for the contractions of our muscle cells, and in the cellular cytoskeleton, and it causes the parallel fibers to contract too. In the course of the interaction between the two types of fibers, the radial fibers began to tilt to the left, and this tilting was self-enhancing, which means that it grew progressively stronger because the fibers affected one another, as in a pile of falling dominoes, ultimately resulting in the swirling.

Why does the swirling always occur in the same direction? The answer is found in the inherent twist present in individual actin fibers. The model has demonstrated that because each actin fiber is shaped like a right-handed helix, held in place at the tip, it should rotate about its own axis during the self-assembly of the cytoskeleton, as indeed happened in the experiment. Thus the asymmetry of a single protein is translated into the asymmetric behavior of the entire cell.

These findings help clarify what kind of “knowledge” a single cell has at its disposal, which, in turn, can advance the understanding of how a lack of left-right symmetry arises during fetal development. In the future, the findings may also be of use in tissue engineering, in which cellular cytoskeleton needs to be created to achieve optimal tissue architecture for various applications – for example, to facilitate wound healing.

Alexander Bershadsky says Singapore’s Philharmonic Orchestra gives excellent concerts that he attends frequently, but this is not the reason he spends part of the year in Singapore. He had been invited to become a founder of the Mechanobiology Institute, created in 2009 at the National University of Singapore as part of that country’s massive effort to advance basic biological research with potential industrial applications. Since then, Bershadsky has been dividing his time between the Weizmann Institute of Science and the Mechanobiology Institute, where he is a visiting professor. The arrangement has proved fruitful, resulting in a number of collaborative studies, the latest of which is described above. Bershadsky has also organized two Mechanobiology Institute Singapore-Weizmann Conferences, one entitled “Symmetry Breaking and Pattern Formation,” held at the Weizmann Institute in 2012, and the other, “Dynamic Architecture of Cells and Tissues,” held in Singapore in 2013.

Alexander Bershadsky says Singapore’s Philharmonic Orchestra gives excellent concerts that he attends frequently, but this is not the reason he spends part of the year in Singapore. He had been invited to become a founder of the Mechanobiology Institute, created in 2009 at the National University of Singapore as part of that country’s massive effort to advance basic biological research with potential industrial applications. Since then, Bershadsky has been dividing his time between the Weizmann Institute of Science and the Mechanobiology Institute, where he is a visiting professor. The arrangement has proved fruitful, resulting in a number of collaborative studies, the latest of which is described above. Bershadsky has also organized two Mechanobiology Institute Singapore-Weizmann Conferences, one entitled “Symmetry Breaking and Pattern Formation,” held at the Weizmann Institute in 2012, and the other, “Dynamic Architecture of Cells and Tissues,” held in Singapore in 2013.