עיתונאיות ועיתונאים, הירשמו כאן להודעות לעיתונות שלנו

הירשמו לניוזלטר החודשי שלנו:

Ants can adjust their foraging activities to match the hunger level of their overall colony just through individual interactions between foragers and their nestmates according to new findings published in eLife.

The study, from the Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel, sheds new light on how a natural cooperative system, which has no central control and in which each individual has only partial knowledge, can achieve regulation. This could offer insight on how we handle some of our own systems that rely on distributed control, for example, the electricity grid and mobile networks.

Forager ants make up only about 10% of an entire colony. They collect food to feed their nestmates, facilitated by a “social stomach” – a crop organ situated upstream of their main stomach. Food collected by a forager ant can either be transferred to the main stomach for digestion, or regurgitated from the social stomach and shared with other ants through a kind of mouth-to-mouth process known as trophallaxis.

“The question is how such a small number of forager ants can assess the current nutritional requirements of their entire colony,” says senior author Dr. Ofer Feinerman of the Weizmann Institute. “How much information regarding the colony’s state must a forager have to be able to fulfill its task? For example, does an ant getting ready to leave for its next foraging trip need to know the level of hunger of each of its nestmates, or is it enough that it knows roughly how hungry the overall colony is?”

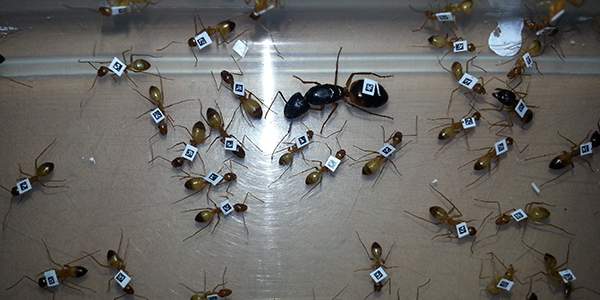

Feinerman and his team used two techniques to discover how the collective goal of colony satiation is achieved by single Camponotus sanctus ants even though they might not necessarily have full knowledge of this goal. Fluorescent imaging allowed the researchers to see into the stomachs of individual forager ants and to quantify how much food was in each. Barcoding the ants with tiny tags enabled them to identify each individual ant during the entire feeding process.

As the colony members ate, the scientists watched the flow and storage of food among them and identified “microscopic behavioral rules” followed by foragers that dictated the rates at which food flowed into the colony.

“We found that foragers deliver food at a rate that depends on the amount of food already stored in the crops of individuals they encounter,” says first author Dr. Efrat Greenwald, a postdoctoral fellow in Feinerman’s lab. “The amount of food that foragers pass to a single nestmate first seems quite random – the receiver is not filled to capacity and the forager does not empty its entire load. Nevertheless, there is a strong link between the amount of food passed to a nestmate and the amount already in that receiver’s crop. The receivers, we found, generally represent how hungry the colony is, and this suggests that food-flow rates are matched to the hunger level of the entire colony. Forager ants can therefore adjust their activities according to the colony’s overall hunger level without knowing explicitly what this is.”

“The next step will be to study the underpinnings of collective nutritional regulation in relation to more complex nutritional challenges, such as choosing between different food sources varying in quality or composition. These are well known to occur in social insect colonies,” says co-first author Lior Baltiansky, a PhD student in Feinerman’s lab. “Looking more broadly to the field of distributed control, in which the inner workings of some of the most common manmade networks are not fully grasped, we may have a thing or two to learn from ants, which are one of nature's exemplars of distributed workings.”

Dr. Ofer Feinerman's research is supported by the Clore Center for Biological Physics; the Clore - Israel Foundation; the estate of Rachmiel Ramon Bloch; and the European Research Council. Dr. Feinerman is the incumbent of the Shlomo and Michla Tomarin Career Development Chair.